Update: Spring 2022

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Gibson Dunn #2), 2018. Collage on paper. © 2022 Buck Ellison. Courtesy of the artist.

Our latest update shares recent art law developments from around the world with insights from our practice

Art Law Studio launched in 2021 with a vision to create a more accessible law firm immersed in the art world and dedicated to art-related matters. We are proud to count leading artists, advisors, collectors, dealers amongst our growing client-base.

A New York Judge ruled this month against Marianne Boesky Gallery in its dispute with the New York-based artist Diana Al-Hadid. The Gallery had funded production costs for an unidentified bronze sculpture by the artist and claimed an ownership interest – but the court held that no such interest was reflected in the documentation between the parties. Pending a possible appeal, the case is a useful reminder that template agreements should always be tailored to reflect the particular circumstances and revisited and updated where – as so often happens – working practices diverge from the original agreement over time.

It is clear to us that the next generation of artists, dealers and collectors is reluctant to rely on the handshakes of the past, prudently preferring to document relationships clearly from the outset. That being said, we often advise on disputes between artists and dealers based in the UK and overseas, working with leading lawyers from our overseas network where matters touch their jurisdictions. In each case, the common thread was poor (if any) documentation of the commercial relationship which seemed unnecessary given the initial trust – followed by a breakdown of trust.

As relationships between artists and dealers become less exclusive - and larger galleries collaborate to show the same body of an artist’s work at the same time (Andreas Gursky’s current shows at White Cube London and Gagosian New York being a case in point) - concise written agreements have never been more important to protect relationships from misunderstanding. Every dispute begins with two parties who think they will not fall out – and in our experience that is the optimal time to reduce the understanding to writing. We always remind clients that contracts will typically favour the party drafting the document and should be reviewed carefully before signing with that in mind.

Rudolf Stingel, ‘Untitled’ (2012): not a photograph and not guaranteed

British-born American dealer Inigo Philbrick was finally sentenced in New York this month to 7 years in prison for masterminding a sophisticated scheme which defrauded experienced and high-profile art investors. Not unlike the scheme of UK dealer Timothy Sammons who was sentenced in New York in 2019, Philbrick’s scheme began to unravel in May 2019 when Rudolf Stingel’s photorealist painting of Pablo Picasso – Untitled (2012) – sold at Christie’s New York for USD 6.5M with premium. Prior to the sale, Philbrick had circulated a document indicating that Christie’s had guaranteed the work would not sell for less than USD 9M (we now know this document was a forgery).

Permanently closed

Philbrick's plea for sentencing leniency gives an overview of the scheme – which involved up to 29 blue-chip art works in transactions valued at USD 86M – and his purported sale of more than 100% of works by Basquiat, Guyton, Judd, Kusama, Stingel and Wool to multiple individuals and entities and use of those works as loan collateral. Whilst the jail sentence brings an element of closure for Philbrick, his victims remain locked in costly civil proceedings to establish the priority of their interests in the underlying artworks. We are following the cases closely and will report on the decisions when rendered. For now, the Philbrick affair highlights the importance of conducting careful due diligence on both the artworks and the people involved in a transaction.

English law places the onus on a buyer of art to conduct due diligence (“buyer beware”) and we see our clients’ appetite for advice increase with a work’s value. Due diligence is the art (and, increasingly, science) of verifying that an artwork is in fact what it purports to be: is it for example authentic, are there condition issues and – as as highlighted by the Philbrick affair – does the seller have good title?

Camille Pissarro, Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain (1897)

Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain (1897) – currently in the possession of Madrid’s Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum – has been the subject of a 17-year title dispute between the Spanish museum and the Jewish heirs of Lilly Cassirer who forfeited the painting to a Munich art dealer in 1939 in exchange for German exit visas. A similar Pissarro work with a slightly less troubled past sold at Sotheby’s in 2019 for around USD 9 million. Lilly’s heirs filed Californian legal proceedings in 2005 after the Spanish museum refused to return the work. As a signatory to the 1998 Washington Principles pursuant to which 44 nations committed to deliver “just and fair” solutions where the heirs of Nazi-confiscated art can be identified, Spain has been accused of hypocrisy. Signalling possible nervousness in the face of public scrutiny, the museum has recently sought unusual protections when lending works from its collection overseas. US and Spanish law take fundamentally different approaches to the ownership of stolen property: whereas the US (like the UK) tends to favour the victim of a theft, Spain (like France) tends to favour a possessor who acquired stolen goods in good faith. The Californian Court had reluctantly held that Spanish law applied and that it was thus unable to “force the Kingdom of Spain or [the Thyssen] to comply with its moral commitments”. A unanimous ruling from the US Supreme Court in April 2022 begs to differ, opening the door to the application of US law and the possible return of the painting to the family. Those wishing to see Pissarro’s masterpiece in Madrid may wish to do so sooner rather than later.

Viennese poster campaign from 2006 featuring Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) - shortly before its restitution from Austria following the high-profile legal dispute depicted by Dame Helen Mirren et al in the 2015 film ‘Woman in Gold’

Most of the laws affecting the art world were not designed for art specifically - and that is particularly evident for copyright law. Copyright law varies by jurisdiction but often struggles to accommodate the practice of appropriation (which cannot exist without the taking and re-contextualising of existing material). In this respect, an April 2022 decision of the Berlin Regional Court - holding that artist Martin Eder’s incorporation of existing digital material into a painting on canvas fell within the “pastiche” exemption - is noteworthy and positive (the UK has a similar copyright exception for pastiche, the parameters of which have yet to be tested in a visual arts context).

Across the Atlantic, the dividing line between acceptable (“fair”) use and illegal copyright infringement will focus the attention of the US Supreme Court later this year thanks to Andy Warhol. The Second Circuit Appeal Court ruled somewhat controversially in 2021 that Warhol’s use of photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 image of pop icon Prince did not constitute fair use. The Andy Warhol Foundation appealed and - whichever way it goes - the SCOTUS decision will be hugely significant; and Warhol will be making headlines once again.

The authorship of conceptual art is currently under the spotlight in France and Germany thanks to the work of Maurizio Cattelan and Martin Kippenberger, raising an evergreen copyright question: Is the “author” the one who conceptualises the work or the one who brings it to life?

Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour), 1999. Image taken at the Guggenheim New York in 2011 by Mark B. Schlemmer from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Between 1999 and 2006, Cattelan and his gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin engaged the French sculptor Daniel Druet to create nine of his most famous and controversial wax effigies including La Nona Ora (1999) – featuring Pope Jean Paul II felled by an errant (or divinely directed?) meteor – and Him (2001) – featuring a penitent, kneeling Adolf Hitler. Perrotin confirmed that Druet and Cattelan “did not talk about a contract” and Druet has filed proceedings in Paris claiming sole authorship of the works plus significant damages. The case has provoked an impassioned response from the French art establishment, with 65 luminaries including Sophie Calle and Annette Messager penning a 14 May 2022 opinion piece for "Le Monde" expressing collective concern that Druet's quest for recognition as sole author of works conceptualised by Cattelan risks the “disqualification of conceptual art”.

Götz Valien, "Paris Bar", Variante 3, 1993–2010

Meanwhile, in Germany, Martin Kippenberger engaged a young painter called Götz Valien to paint two versions of the interior of “Paris Bar” – a popular haunt for Berlin artists – in 1991 and 1993. The works built on Kippenberger’s 1981 series painted by a professional poster artist at his direction entitled “Lieber Maler, male mir” (“Dear painter, paint for me”). The 1991 version of “Paris Bar” sold at Christie’s in 2009 for € 2.5m and the 1993 version is in the Pinault Collection. In 2010, Valien made an identical version of the 1991 work which he attributed to himself - raising the question of whether Valien’s 2010 work infringes copyright in the 1991 work (despite having painted both works himself). No proceedings have been filed to date by the Kippenberger Estate and, candidly, we imagine they are unlikely given the artist’s well-known objection to the notion of the artist as singular genius.

Absent prior agreement between the parties, authorship under French and German law would likely turn on the instructions from Cattelan and Kippenberger: the more specific the instructions, the less opportunity Druet and Valien would have had to impart their own intellectual creation on the final work which might in turn amount to joint authorship (the basis of Druet’s claim for sole authorship of the Cattelan-conceived works is unclear to us). We are following the cases with our French and German colleagues and will report further in due course. In the meantime, the cases highlight the importance of clear agreements at the outset when collaborating with third parties - regardless of artistic medium - to ensure the artist retains all IP. Where parties decline this opportunity, the law will always step in to find a solution.

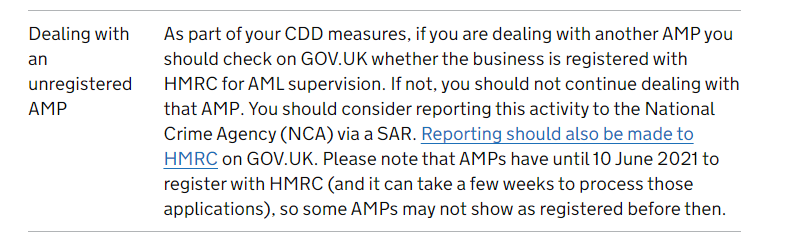

Finally, our recent post described the UK’s anti-money laundering (AML) regime for “art market participants” (AMPs) trading in works of art above the €10,000 threshold. Since the new rules were introduced in early 2020, the list of registered AMPs has grown steadily to over 900 today. UK Government Guidance directs AMPs to check the list and not deal with unregistered AMPs (see image). We understand HMRC are now undertaking audits and AMPs trading whilst unregistered – or without the appropriate/updated compliance documentation – risk being identified, fined and publicly censured. We would encourage AMPs to seek advice as necessary to minimise fines and penalties.

UK Government guidance: beware of unregistered “art market participants”

This report and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. Specific legal advice on your particular circumstances should be obtained before taking or refraining from any action after reading its contents. Please contact us if you need advice.